Original Sin

Original Sin gets a bad rap, in large part due to its (later) ties to sex. Although Augustine often gets blamed, the gnostics were equally if not more responsible. Augustine perceived life as beautiful but confusing. That is, creation was beautiful. Human beings were something else.

A great deal of gnosticism, however--despite contemporary efforts to paint it as some kind of non-sexist, life-is-beautiful 1960's forerunner--was about as anti-the-physical-experience as intellectuals can (and still do) get. Gnosticism could also get intensely elitist.

Original sin, as Alan Jacobs points out, had the merit of at least being universal. Everyone--kings to peasants--was so tainted. And early Christianity was far less obsessed with the supposed logical ramifications (why would God allow us to be evil?) than later Christianity. Most people, from Paul to Erasmus, accepted that humans just, well, made mistakes and did dumb things. Of course, they required salvation!

Original sin, as Alan Jacobs points out, had the merit of at least being universal. Everyone--kings to peasants--was so tainted. And early Christianity was far less obsessed with the supposed logical ramifications (why would God allow us to be evil?) than later Christianity. Most people, from Paul to Erasmus, accepted that humans just, well, made mistakes and did dumb things. Of course, they required salvation!

The Protestant Reformation and the Enlightenment brought about an almost obsessive need to explain the origin of bad behavior in humans. The world seems to have split into those who said, "Well, sure, humans do bad things. Welcome to being human. Why else would we need grace?" and those who said, "But it doesn't make sense that a perfect pure God could allow so much nastiness. Therefore..."

And entire generations of believers tied themselves into knots.

It occurred to some people to separate outcome from intent (transgression versus sin). But they were often shouted down by people who praised the majesty of God and then behaved as if God was something they had tucked into their back pockets (this blogger takes the view of C.S. Lewis: Deity is not a TAMED lion).

It occurred to some people to separate outcome from intent (transgression versus sin). But they were often shouted down by people who praised the majesty of God and then behaved as if God was something they had tucked into their back pockets (this blogger takes the view of C.S. Lewis: Deity is not a TAMED lion).

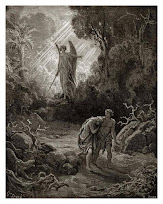

The expulsion from the Garden of Eden consequently became a more and more contentious issue. While Early Christianity argued fiercely over the nature of God (half-human/half-God or all-human/all-God or something else), later Christianity was more concerned with the nature of humankind and that issue was heavily complicated by the problem of free will. Free will was always on the table. Paul takes it for granted. Later Christians, however, wanted to square it with a whole host of other ideas.

Calvinism in America threw itself into the deep end by wanting to apply fate to people's souls beyond birth while embracing free will as well as rational explanations for stuff. And one of the easiest rational explanations (on the surface) has always been to figure out who is to blame.

Adam as the guy at fault (humanity would be so happy if only Adam and Eve hadn’t…)

was omnipresent enough as a theological argument in the nineteenth

century for the 3rd Article of Faith (written down by Joseph Smith and

his early followers) to state, “We believe that men will be punished for

their own sins, and not for Adam’s transgression.”

Adam as the guy at fault (humanity would be so happy if only Adam and Eve hadn’t…)

was omnipresent enough as a theological argument in the nineteenth

century for the 3rd Article of Faith (written down by Joseph Smith and

his early followers) to state, “We believe that men will be punished for

their own sins, and not for Adam’s transgression.”

Because, of course, blaming Adam didn’t really help matters either since, as mentioned earlier, Why would God allow Adam’s fault to impinge on us? Why would God set up humans to fail? Why would he give them natures that couldn’t get better? How far does grace go to wipe all that out? Is it fair to override people’s bad actions? Do murderers go to heaven? Why not? Doesn’t God want humans to be happy? (Happiness is a big issue in the nineteenth century.)

In Alma 42, Joseph Smith attempts to solve the problem of blame and the Garden of Eden, an approach that he brings into focus in the Book of Moses.

To be continued...

No comments:

Post a Comment