|

| The meaning of Eden is part of the struggle. |

1 Nephi 14-22: Grace & Works

The

Book of Nephi begins a struggle over hell and grace and punishment that

continues throughout The Book of Mormon. It was an ongoing struggle in

the nineteenth century as well as today! That struggle is arguably part

of the human condition.

Nineteenth-century readers would have had personal contact with this struggle, being familiar with Arminianism—God’s grace is universal—and Calvinism—pre-ordination of salvation. In America, the struggle came down to Methodism versus what had become by that time Congregationalism (the latter term now has a broader use).

So hell as punishment is a given. However, in Nephi’s

interpretation of Lehi’s dream, the quality or character of hell is

defined: “And I said unto them that the water which my father saw was

filthiness; and so much was his mind swallowed up in other things that

he beheld not the filthiness of the water” (1 Nephi 15:27, my emphasis).

So hell as punishment is a given. However, in Nephi’s

interpretation of Lehi’s dream, the quality or character of hell is

defined: “And I said unto them that the water which my father saw was

filthiness; and so much was his mind swallowed up in other things that

he beheld not the filthiness of the water” (1 Nephi 15:27, my emphasis).

Although the passage about hell may seem rather harsh—and a bit skimpy on the grace side—nineteenth-century readers would have seen it as bolstering the idea of universal grace: hell is not the place where people who didn’t complete all the correct rituals or joined the right congregation go (it isn’t group-identity hell). It isn’t a place where people go whether or not they worked hard not to go there. It is the place where individual “filthy” people go.

Religious designation is not a qualifier. Neither is race. Neither is birth. This perspective would have been perceived in the nineteenth century as provocative. (Readers are being prepared for a complete rejection of infant baptism.)

2 Nephi and Jacob: Grace & Works Background Up to the Nineteenth Century

2 Nephi and Jacob: Grace & Works Background Up to the Nineteenth Century

Two problems underscore much religious discourse. Those problems have a long history:

- The problem of grace versus works—that is, the problem of a deity's mercy versus human merit.

- The problem of the elect or elite, those who are supposedly entitled to God’s mercy and intervention.

At this point, I will turn to etymology—then I will return to the nineteenth century.

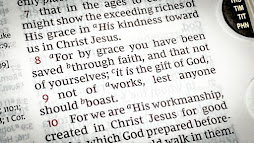

In James’s statement, “Faith without works is dead” the word “works” is based on a Greek word, ergon, which refers to “energy.” The word is connected to the business of agriculture and trade—that is, it is connected to multiple roles that people may take in a community. (I did not know this background information for myself: see this site here.)

That is, faith without energy is meaningless because faith without energy means a person is dead.

We wake up in the morning. We get out of bed, feed the cats, carry out tasks, open mail. Everything is something we do

as living people. And during all of that, we ponder stuff, which

arguably is also an action in which neurons leap the boundaries between

synapses. Faith is, in fact, ongoing agency, a position that The Book of

Mormo commits to doctrinally (see 2 Nephi 2:26).

That is, “works” as defined by Martin Luther et al. became actions that by themselves don’t appear to have a moral component but have been turned into a moral necessity: good people jump through these hoops; use these phrases; perform these routines; make these mea culpas.

The issue becomes complicated because not all rituals are meant to be works. Sometimes, they are meant to be reminders of faith or inductions into cultural belonging. A signal of commitment.And Protestants rapidly split into those who despised all rituals, including any custom that took place in any church or within any religious group, and those who said, “Uh, you folks are kind of throwing out everything at once.” (Forensic anthropologists are not very happy with Protestant zealots in England who threw out Anglo-Saxon saints’ bones that can now not be tested.)

See the posts Why Choosing the Supposedly Correct Side is Difficult.

To nineteenth-century American readers, “works”—on the one hand—smacked of Catholicism, the corrupt Old World, and stuff like worshiping saints. On the other hand, early Protestantism almost immediately created its own sets of “works.” Good religious people embrace the following lifestyle and use the following language and support the following celebrities/political causes…

And the truth is, every culture, by the nature of being composed of non-dead and human people, is going to have “performances,” stuff that people do because that’s part of being a member of a community. (We even create “performances” in our personal lives/routines.) If we decide that only “meaningful” actions should be carried out, we run the risk of ending up as humorless as, well, a bunch of Woke Puritans who burn Maypoles, close down theaters, get offended over single words and phrases, and lecture others on supposedly bad thoughts.

Joseph Smith was not a guy who lacked a sense of humor.

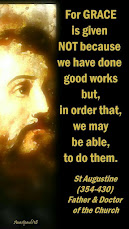

In opposition to “works” is the principle of grace. Saint Paul argues that we are saved by grace. Full stop. Not “after all we can do.” We are saved by grace. Propitiation is off the table. God doesn’t bargain. And humans aren’t meant to be grifters. Give it up.Yet even Paul struggled with the reality of communal living and the irritation of people doing petty things like, say, suing each other. And he also had a sense of humor.

In

sum, if one sets aside the "performance" side of works, the issue of

grace v. works/action/energy still remains: Do humans earn God's

attention? Or does God offer attention? Does God react based on merit?

Or is merit human wishful thinking?

God is bigger than us and can do what He wishes, so we are saved. But sometimes people are jerks. And sometimes they walk away from God. And sometimes they think they have walked away but they haven’t. And sometimes they think they haven’t but they have. And how fair is it really for a jerk to be saved? (According to Jesus Christ and the parable of the workers, Entirely fair and so not your business.) And since we do get up every morning and do stuff, shouldn’t that stuff be moral? And if we claim to love God, shouldn’t there be a connection between that love and the moral stuff we do?

Do we work our way towards the infinite by a checklist? Or by learning and growing? Or by being loved and accepted?

I consider Christianity one of the most fascinating religions on record simply because it hauls this problem to the surface and doesn’t fully answer it. The Book of Mormon and its translator, for instance, will return to the problem over and over again. Why not? The Book of Mormon’s initial readers were struggling with it as much as Paul’s audience and modern believers.

Later entries on this blog will return to the issue of grace & works.

No comments:

Post a Comment